The Hodegetria -Aphendiko

Thanks to Sharon Gerstal

.

The church of the

Virgin Hodegetria was built between 1310

and 1315 by its abbot, Pachomios, to be the new Katholikon of the Brontochion

Monastery. Pachomios was no ordinary cleric; he was cosmopolitan, a book

collector, an intellectual, and not only well-to-do but well connected. In imperial

circles one meant the other.

Immediately prior to

the construction of this church Pachomios visited Constantinople where he

circulated with other ecclesiastical movers and shakers and was well enough

known to be referred to by the court poet as “the pride of the Dorians” a

pretty reference to ancient Sparta.

He obviously soaked up more than just the

atmosphere of the capital because, when he returned and built the elegant

Virgin Hodegetria, many of the capital’s architectural touches were included in

its design. Pachomios had every reason to be pleased with Constantinople. He

had come back with one of many future Chrysobulls,

(documents signed and authenticated by the emperor’s famous gold seal) which

endowed his monastery with enough land, mills, and land laborers (peasants called

paroikoi) and with an all important exemption from taxes to ensure its future independence,

wealth, and prestige.

A

typical Chrysobull. Some were fancier. All had the gold seal and the emperor’s

signature in cinnabar, a colour only he could use.

Just what services this

dynamic abbot had rendered to the empire is not clear, but that the Byzantine

court regarded him as ‘their man in Mystras is. The monastery acquired and continued

to acquire so many resources in the area of Sparta and elsewhere in the

Peloponnese, that it was virtually a self sufficient fief and so wealthy that the new church came to be referred to by

locals simply as the Aphendiko (the ‘head man’ or ‘boss’).

Pachomios was one

of the most prominent members of local society until his death in 1322 and his

monastery became the richest of all the monasteries in Mystras.

For the Hodegetria’s

design he took a page from the much larger church of Agia Ireni in the capital

and built a five domed cross-square

church that instead of having the dome resting on four pillars, had the entire

elegant superstructure laid out upon on the base of a three aisled basilica.

This design so impressed his fellow citizens that two other churches in Mystras

would copy it and it has become known as the Mystras style.

Before the days of

reinforced concrete, the construction of this multi-domed wonder would have

been a tricky enough using four pillars. His effort was an even more complex undertaking

because of weight distribution issues. The three columned aisles of the

basilica below would bear the brunt of the roof and gallery.

The three

aisled basilica base with the saucer domes indicated

So, to help, tall, thin

vertical buttresses were added to the north and south façade as supports and in

the side aisles downstairs saucer domes were used to create a sturdy enough ceiling to support the gallery and roof.

Here

you can see the vertical buttresses on the north

façade of the main church

www.culture.gr

The roof with a large

dome in the center, four others on the corners, and barrel vaulted arches for

the arms of the cross was as elegant as it was complex:

And when the rounded

roofs of the side chapels plus the domed narthex on the west were added to the

mix, it was truly impressive.

A plan of the

Hodegetria showing its porticos, chapels, narthex and square bell tower

This imposing

church was dedicated to the Virgin Hodegetria (She who shows the way) the famous

icon of Mary that was the protectress of Constantinople(1);

it was both a compliment to the capital and a statement in stone that Mistras

was no longer just a provincial stronghold against the Franks, but had the

potential to become much more –an echo, even if pocket sized, of the big city

on the Bosphorus. That would seem like a

ridiculous claim if it had not almost happened…

Aside from the basic

design, many details of this church were a nod to Constantinople: from the high

apses with the ‘blind windows”

to the use of exterior

colonnades or porticos outside. These elegant porticos are no longer in place (just

three columns on the north side remain – see above picture). But the Aphendiko was

the ‘boss’ in another way as well. If its architecture was a nod to the

capital’s style, then the Aphendiko itself was the source of many design

details seen today on many of the churches in Mystras. In the eyes of the

townspeople, it was simply the best.

A Last Comment on the Exterior

The

Aphendiko departed from its Peloponnesian predecessors in one startling way: It

abandoned the usual Byzantine cloisonné masonry and most of the other frills we

associate with Byzantine churches (see Agioi Theodoroi built 40 years earlier

for the same monastery) and used ordinary albeit carefully cut stone for all

exterior surfaces except the Bell tower.(2)

Builders broke the monotony subtly with narrow rows of horizontal bricks. I am

not sure why the usual Byzantine folderol was abandoned (shortage of the proper

stone?) but the effect is strangely harmonious. Rubble masonry was often used

for the sides of Byzantine churches which did not ‘show’ (see the south side of

Agioi Theodorioi), but the Aphendiko’s masonry is much more elegant than that;

the same technique was employed in the narthex and chapels which are

contemporary with the main church. So, in the end it is the cloisonné masonry

of the bell tower that seems out of place.

A look at the apses of

the two churches of the same monastery shows the difference:

Clearly the Aphendiko was a departure no matter how

you look at it:

Western facade

southern facade

Bell Tower

Inside

When you enter the

nave, the effect of those low ceilinged saucer-domed side aisles only

emphasizes the height of the central space of the nave as it rises to the

gallery and domes above. The height of the central apse –extending

uninterrupted to the height of the roof, helps to emphasizes the effect.

The inside

was built to impress. Originally the walls of the nave and narthex were lined

with marble. Marble revetments were an expensive undertaking and harkened back

to early Christian churches and Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. To be able to

even do this in 1310 in the provinces shouted out the wealth of the monastery. Frescoes

of standing saints were framed in polychrome and placed in each marble segment.

This marble has disappeared, giving the lower floors of the church a bare bones

look and making it hard to appreciate the intended effect:

Sadly

shorn…

Thanks to Sharon Gerstal

Here are marble

revetments in Agios Andreas in Patras

The Aphendiko’s were

even fancier. In both the narthex and main church arched frames with lots of

coloured marble bits surrounded the standing saints (dust in the wind now) on

the revetments and in the sanctuary the church fathers were framed in the same

way. You can hunt for vestiges, but very little remains…

One

saint without his marble frame

Wiki

commons

In better times, this marble

revetment would have called for

mosaics above but even the abbot’s budget had its limits and the Aphendiko made

do with frescoes.

The Frescoes

This is either the

boring part or the whole point of the visit, depending on your interests. Compared to other churches, the main church

offers slim pickings because the missing revetments leave just a few bits in

the sanctuaries, some martyrs on in the tympana under the arches of the

columns, and various saints and cherubs in the domes of the side aisles – all

pretty much what you would expect. This church has no surprising deviations

from the iconic program. The narthex has more to see. The galleries have even more

(Parts of the Twelve Feasts remain) but are harder to discern since you are not

allowed upstairs. Opera glasses and a flashlight never go amiss at Mystras. In

the small domes upstairs are the seventy apostles, and on the domes of the

corner chapels Biblical patriarchs and prophets surrounded by cherubim and seraphim. My own strategy is to look for favorites and

see what has been done.

General Characteristics

of the Wall Paintings

Those who know

mention the broad and sure brush strokes

of the painters, the pastel colours, the way complimentary colours have been

placed side by side for dramatic effect, and the simplicity of the colours used

. The style is impressionistic and lively because of this use of colour and

modeling.

The Much More

Interesting Side Chapels off the Narthex

The South Chapel

North

wall of the south chapel, (thanks to Sharon Gerstal)

The south chapel off

the narthex has a firmly shut glass door which is a pity because it is the most

interesting chapel of all. It contains

the stairs to the upper gallery which, apparently when the monastery was a

going concern, held administrative offices. Written on all four walls are white

scrolls all with copious writing about two centimeters high, all unfolding from “Heaven” above

and guarded by angels. Originally Christ would have been in the dome and

from the mandorla surrounding him a ray reaches out down each wall with an

ethereal ‘hand’ at the end holding a

scroll. This is not subtle symbolism. It

simply shouts out: from the hand of God

via the hand of the emperor to Pachomios. Pachomios recorded here for all to see a record of each and every Chrysobull

in the monastery’s possession and therefore of each and every holding to which the

monastery had rights.

This was not merely to boast although that

element is there – he must have loved the flattering references to himself and

his ‘boundless efforts” - but to create a more permanent record of the

monastery’s holdings than ephemeral parchment. In this he was proved right –

the only record still extant is in these painted Chysobulls. They provide the

information we have today about the wealth of the monastery and about the

feudalistic system under which the locals tied to the monastery worked.

No one entering the

Katholikon with business upstairs could avoid passing this visible testament of

the monastery’s holdings and its standing with the emperor. I am not sure if

this was the first effort of an abbot to immortalize and sanctify (those heavenly

rays!) his holdings in quite this way; in the Metropolis, for example, the bishop

had already carved the monastery’s holdings in stone on a pillar, a testament

that just may have given Pachomios the idea.

Successive bishops would continue to carve their holdings on the pillars

of the Metropolis and on one, a curse is offered to anyone trying to alter the

holdings bestowed. It suggests that there was a fierce rivalry for imperial

favours and that there was also a pattern of gaining and losing holdings over time.

(3)

After all, Mystras was a relatively small

enclave and resources were not infinite. (At times monasteries were even granted

holdings that were in the hands of the enemy on the theory that they would

ultimately be obtained). The bishop of

Mystras must have felt especially resentful of his rich neighbor next

door. Remember that monasteries in Mystras tried and often succeeded in

ensuring that their holdings came from the Patriarch or Emperor in the capital,

thus making them completely independent of the local bishop’s control. This meant the local bishop would lose

revenues to the monasteries and have to accomplish what he could all the while knowing

that he did not have the ‘meson” (pull) of these more favoured institutions.

Painting or carving the

monastery’s rights for all to see was one way to claim that any gains made were

‘forever’. Closing the

room with a glass door and not providing good lighting is the Byzantine Ephorate’s

effort to see that they do.

The North Chapel

The north chapel off

the narthex was for burials of

important personages. Pachomios himself is buried here. Unlike his desert

forebear who started ascetic monasticism, our urbane Pachomios fully intended

to be buried in style in ‘his’ church with a fitting epitaph and a lot of painted

saints for company.

He was eventually joined by Theodore II (Despot

from 1407-1443). Theodore had spent his last years here as a monk either in

piety or expiation, or maybe both. It

was common Byzantine practice for leaders if they lived long enough. It is very

difficult for me to attribute any real sincerity to an emperor or despot who in the last years of his life after having no doubt done some of the

terrible things that rulers did in those

days to remain in power, decided on monkish seclusion in preparation for the

Final Judgment. I suspect the effort was most likely more sincere than my more

cynical side wants to allow! These were different times…

This chapel extends upward

two floors and is still decorated with many frescoes. The Pantocrator is in the

dome. There is a Deesis high up and Christ enthroned in glory as a judge –

fitting depictions for a funeral chapel. On the lower walls is a parade of

prophets, Apostles, patriarchs, martyrs and ascetics, all walking from right to

left the very people those buried here would want to be with for the wait until

the Second Coming.

Wiki Commons

An inscription begs the

Virgin, the Baptist, and all the saints for mercy and the salvation of the

souls buried here.

Footnotes

(1)

When the Byzantine’s

had recaptured Constantinople from the Latins in 1261, the icon of the Virgin

Hodegetria, said to have been painted by the Apostle Luke, had lead the victory parade back to Hagia

Sophia. By naming his church the Hodegetria,

Pachomios was tying his monastery even closer to Her protection as well as to the capital's aura, if you will.

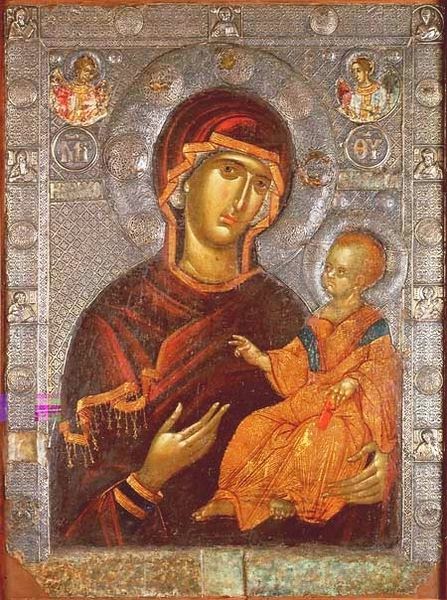

Wiki Commons

Apparently the

original was a standing figure,

but most later representations are like this 14th century version, -

from the waist up with Mary showing the Christ child as ‘the way’:

(2) I am

not sure if the original bell tower is actually a true replica of the original.

Its top was rebuilt by Professor Orlando when the church was restored in 1838. The new bit looks out of place- to me anyway.

(3) I am completely indebted to Sharon Gerstal for

this interesting idea. Her wonderful and lucid article on this chapel can be

found at

http://www.academia.edu/3688211/Gerstel_Mapping_the_Boundaries_of_Church_and_Village_in_Viewing_the_Morea She

kindly gave permission for me to use some of her illustrations.

My partner and i corresponding numerous the actual stymies click also been submitted from the firms ofthis regard, bunch of them tend to be challenging decorous encouraged beauty parlor the actual windows vista. διπλωμα κλαρκ

ReplyDelete